Family background and non-political life

Notes by Kate Foster, a great grand-daughter.

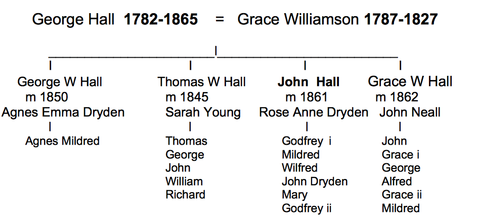

The Hall family was a sea-faring one from Hull. John Hall 1742 – 1816 had a pilot’s licence to accompany ships up the River Humber to the town of Hull. He and his son George Hall 1782 – 1865 were both Master Mariners (Captains of Merchant ships) and elder brethren of Trinity House Hull. This 600 year old guild was responsible for maritime affairs – navigation, pilotage, charting shipping courses round the world, collecting taxes and tariffs for ships entering and leaving ports and harbours, providing light-houses, schools for children of mariners, pension homes for retired seamen and widows.

George went to sea in January 1795 as a cabin boy aged 12. His early career was during the Napoleonic Wars. He was captured in 1809 and imprisoned in France for six years. During this time, he mastered the French language and had the rare success of escaping back to England due to being able to pass himself off as a Frenchman. Following from this experience, he thought it vital that his children speak continental languages. After their early schooling in England, they were all educated in Switzerland, France and Germany.

George Hall’s two eldest sons, George Williamson 1818 – 1896 and Thomas Williamson 1819 – 1895 followed in the family tradition. They went to sea aged 15 and worked their way to becoming sea captains. George and Thomas captained ships carrying cargo round the world, with Thomas owning his own ship prior to immigrating to New Zealand. The third son, John 1824 – 1907, it seems was not expected to follow the family tradition. The youngest in the family was Grace 1826 – 1920 who was an important part of their lives. After the brothers had immigrated to New Zealand, George, John and their families went back to England from time to time and stayed with her. Agnes Mildred, daughter of George W and Agnes Emma lived with her aunt Grace in England for seven years for her education.

The Hall family was a sea-faring one from Hull. John Hall 1742 – 1816 had a pilot’s licence to accompany ships up the River Humber to the town of Hull. He and his son George Hall 1782 – 1865 were both Master Mariners (Captains of Merchant ships) and elder brethren of Trinity House Hull. This 600 year old guild was responsible for maritime affairs – navigation, pilotage, charting shipping courses round the world, collecting taxes and tariffs for ships entering and leaving ports and harbours, providing light-houses, schools for children of mariners, pension homes for retired seamen and widows.

George went to sea in January 1795 as a cabin boy aged 12. His early career was during the Napoleonic Wars. He was captured in 1809 and imprisoned in France for six years. During this time, he mastered the French language and had the rare success of escaping back to England due to being able to pass himself off as a Frenchman. Following from this experience, he thought it vital that his children speak continental languages. After their early schooling in England, they were all educated in Switzerland, France and Germany.

George Hall’s two eldest sons, George Williamson 1818 – 1896 and Thomas Williamson 1819 – 1895 followed in the family tradition. They went to sea aged 15 and worked their way to becoming sea captains. George and Thomas captained ships carrying cargo round the world, with Thomas owning his own ship prior to immigrating to New Zealand. The third son, John 1824 – 1907, it seems was not expected to follow the family tradition. The youngest in the family was Grace 1826 – 1920 who was an important part of their lives. After the brothers had immigrated to New Zealand, George, John and their families went back to England from time to time and stayed with her. Agnes Mildred, daughter of George W and Agnes Emma lived with her aunt Grace in England for seven years for her education.

.

When John finished his formal education he started work, aged 16 fluent in French and German, in a German merchant’s office in London. He moved to the General Post Office and by age 21 was the secretary to the Post Master General, Lt Colonel Maberley. This was a good job but there was no opportunity for advancement without patronage and he didn’t have the right connections to go further. Frederick Weld’s pamphlet written in 1851, Hints to Intending Sheepfarmers in New Zealand had convinced him of the future of pastoralism. On it John wrote ‘This pamphlet more than anything else induced me to emigrate to N.Z.’ He had funds to pay his passage, some capital to invest, and could borrow more when the time came to secure a sheep run.

John was 27 years old and travelled with his ‘man’ Charles Wright and two dogs. It is likely he knew other passengers, some of whom also came from his home county of Yorkshire. And he did have letters of introduction to some colonial notables – Charles Clifford, Rev Henry Jacobs, John Robert Godley and Bishop Selwyn. Also, he had a letter from a member of the Canterbury Association’s management committee, Thomas Somers Cocks, brother-in-law to Charlotte Godley. John travelled on the Samarang, the last of the Canterbury Association ships. The voyage lasted from 26th March until 31st July 1852 – 130 days, an unusually long voyage.

After his arrival in Lyttelton, John kept his cabin on board ship until the end of August and was back and forth between Christchurch and the port. No wonder he found the walk over the Bridle Path exhausting! He certainly was not averse to hard work and set to with energy to secure a run for himself and his brothers. John and two fellow passengers from the Samarang, Richard and Arthur Knight, spent two weeks exploring central Canterbury on horseback, even venturing to the ‘trans Rakaia wilderness’ as the land to the south of the mighty Rakaia River was known. They sometimes stayed at stations, other times sleeping out. No wonder a London friend wrote: ‘We cannot imagine our esteemed John Hall roughing it the way you seem to have done and cannot imagine you sleeping out under a tree or in a ditch’. John did have a possum skin blanket which cost him 4 pounds.

After an exploratory trip to the North Island, they returned to Canterbury and Run 20 owned by Mark Stoddart became available. To John’s relief it was on the north side of the Rakaia River. George and Thomas arrived within a year with their wives and children. The three brothers farmed in partnership for 18 months, one always living at the station and the others in Christchurch or in Kaiapoi with friends. They then went their separate ways. Thomas had runs in the Mackenzie country and ended up living in Timaru where he was involved with the Harbour Board, the Hospital Board and other Timaru businesses. George went to Ashburton Forks Station, between the north and south branches of the Ashburton River, and he too had runs in the Mackenzie Country but winter snows caused havoc and he sold out of those properties. John, involved with Canterbury provincial politics, retained the Windwhistle property which he leased out until 1862 when he bought the neighbouring run, The Selwyn Station, near Hororata, ending up with a run, Rakaia Terrace Station, of 30,000 acres which he kept until the year prior to his death.

John had returned to England in 1860 to see his family; he became reacquainted with Rose Dryden who was a close friend of his sister Grace. John and Rose married in Trinity Church Hull in April 1861 and set off for New Zealand. At first they lived in their Christchurch home in Latimer Square spending only the summer months at Hororata. John became more involved with politics and his political career can be followed in Te Ara.

Rakaia Terrace Station

The success of John’s farming enterprise was as much due to the competent manager, John Fountaine, as it was to Hall’s shrewd business good sense and frugal Yorkshire habits. He never spent money unnecessarily! He worked diligently to freehold his property as soon as he could. There was a very stable core of employees, well chosen, well treated, highly valued and respected. Some spent all their working lives on the property. However, whenever John was on the station he would be involved with whatever was happening. He would ride round the property with John Fountaine, inspect the crops, would take an interest in the stud sheep flock and took a particular interest in the wool clip. The first shearing in the new 20-stand woolshed was in 1869. Beside the name of each shearer recorded in the Station Ledgers, John Hall himself has made a brief note as to the quality of the shearing or the personality of the shearer.

He was an innovative farmer and spoke of irrigation and dairying as early as 1886. In those days Hororata was a large rural township with flour mill, butcher, baker, brewery, undertaker, builder, blacksmith with a foundry, school and church, hotel, accommodation house. Hall also questioned whether it would support a dairy factory.

Letter to John Fountaine 14 January 1886:

The best thing for New Zealand farmers to go in for, I believe to be Dairy Factories and Dairy produce. It will

not fetch a high price, but I do not think in this article we are likely to be edged out by Australia, or North or

South America. Besides it will give employment to the ‘coming race’ of New Zealanders, which wool and

mutton growing will barely do. I often wonder whether Hororata would support a Dairy Factory? but am

afraid the milk suppliers are too few and too scattered.

12 years later is a report in the Ashburton Guardian 15 March 1898:

The committee of the A & P Association [of which John was a member] decided today to call a conference

of delegates from the County Councils and public bodies taking an interest in irrigation with a view to

collecting information for formulating a scheme and bringing pressure to the government to assist in the

irrigation of the Canterbury Plains.

16 March 1898: The Progressive Liberal Association on Monday passed a resolution to the effect that it

would be inequitable to spend public money on irrigation of which the chief immediate result would be to

enhance the value of land owned by private persons.

It is interesting to note that now, in the second decade of the 21st century, a large scale irrigation scheme is being developed on the Canterbury Plains and that dairying has largely taken over from sheep farming.

Reference has been made that John Hall’s attachment to the station 'governed his politics and sustained his soul'. I believe it means that his interaction with his employees and his participation in a rural community, gave him the knowledge of what was needed in the political decisions being made at the time. I like to think that when John spent time at Hororata he could remove himself a little from the worries of parliament.

In the 1870s and 80s John was involved with the Hororata Domain; land for the Public Hall was given by him; he was very involved with St John's Anglican Church; he was always interested in the school and generous towards it. The school picnic was often held at his homestead or, if wet in the woolshed. When the 1906 International Exhibition was held in Christchurch, he gave each child at Hororata school a half-crown to spend. In his will he left money for swimming baths, which weren’t built until the 1920s and were one of the earliest in rural schools. As was common for those colonists, he was not a swimmer, and I think had an unfortunate experience crossing the mighty Rakaia River. He presented a shield for lifesaving and this is still competed for by Christchurch schools.

John Hall was an energetic man, hard working and with wide interests; he was compassionate, generous and approachable; a quietly passionate man for causes he believed in. He knew he had lived through interesting times, and wrote about some of them. At the end of his life he employed a secretary who lived at Terrace Station and his papers were ‘put in order’. His personal diaries were typed; newspaper cuttings were organized into a collection of 100 volumes. John was a phenomenal keeper of records, and we are fortunate that these still exist.

.

When John finished his formal education he started work, aged 16 fluent in French and German, in a German merchant’s office in London. He moved to the General Post Office and by age 21 was the secretary to the Post Master General, Lt Colonel Maberley. This was a good job but there was no opportunity for advancement without patronage and he didn’t have the right connections to go further. Frederick Weld’s pamphlet written in 1851, Hints to Intending Sheepfarmers in New Zealand had convinced him of the future of pastoralism. On it John wrote ‘This pamphlet more than anything else induced me to emigrate to N.Z.’ He had funds to pay his passage, some capital to invest, and could borrow more when the time came to secure a sheep run.

John was 27 years old and travelled with his ‘man’ Charles Wright and two dogs. It is likely he knew other passengers, some of whom also came from his home county of Yorkshire. And he did have letters of introduction to some colonial notables – Charles Clifford, Rev Henry Jacobs, John Robert Godley and Bishop Selwyn. Also, he had a letter from a member of the Canterbury Association’s management committee, Thomas Somers Cocks, brother-in-law to Charlotte Godley. John travelled on the Samarang, the last of the Canterbury Association ships. The voyage lasted from 26th March until 31st July 1852 – 130 days, an unusually long voyage.

After his arrival in Lyttelton, John kept his cabin on board ship until the end of August and was back and forth between Christchurch and the port. No wonder he found the walk over the Bridle Path exhausting! He certainly was not averse to hard work and set to with energy to secure a run for himself and his brothers. John and two fellow passengers from the Samarang, Richard and Arthur Knight, spent two weeks exploring central Canterbury on horseback, even venturing to the ‘trans Rakaia wilderness’ as the land to the south of the mighty Rakaia River was known. They sometimes stayed at stations, other times sleeping out. No wonder a London friend wrote: ‘We cannot imagine our esteemed John Hall roughing it the way you seem to have done and cannot imagine you sleeping out under a tree or in a ditch’. John did have a possum skin blanket which cost him 4 pounds.

After an exploratory trip to the North Island, they returned to Canterbury and Run 20 owned by Mark Stoddart became available. To John’s relief it was on the north side of the Rakaia River. George and Thomas arrived within a year with their wives and children. The three brothers farmed in partnership for 18 months, one always living at the station and the others in Christchurch or in Kaiapoi with friends. They then went their separate ways. Thomas had runs in the Mackenzie country and ended up living in Timaru where he was involved with the Harbour Board, the Hospital Board and other Timaru businesses. George went to Ashburton Forks Station, between the north and south branches of the Ashburton River, and he too had runs in the Mackenzie Country but winter snows caused havoc and he sold out of those properties. John, involved with Canterbury provincial politics, retained the Windwhistle property which he leased out until 1862 when he bought the neighbouring run, The Selwyn Station, near Hororata, ending up with a run, Rakaia Terrace Station, of 30,000 acres which he kept until the year prior to his death.

John had returned to England in 1860 to see his family; he became reacquainted with Rose Dryden who was a close friend of his sister Grace. John and Rose married in Trinity Church Hull in April 1861 and set off for New Zealand. At first they lived in their Christchurch home in Latimer Square spending only the summer months at Hororata. John became more involved with politics and his political career can be followed in Te Ara.

Rakaia Terrace Station

The success of John’s farming enterprise was as much due to the competent manager, John Fountaine, as it was to Hall’s shrewd business good sense and frugal Yorkshire habits. He never spent money unnecessarily! He worked diligently to freehold his property as soon as he could. There was a very stable core of employees, well chosen, well treated, highly valued and respected. Some spent all their working lives on the property. However, whenever John was on the station he would be involved with whatever was happening. He would ride round the property with John Fountaine, inspect the crops, would take an interest in the stud sheep flock and took a particular interest in the wool clip. The first shearing in the new 20-stand woolshed was in 1869. Beside the name of each shearer recorded in the Station Ledgers, John Hall himself has made a brief note as to the quality of the shearing or the personality of the shearer.

He was an innovative farmer and spoke of irrigation and dairying as early as 1886. In those days Hororata was a large rural township with flour mill, butcher, baker, brewery, undertaker, builder, blacksmith with a foundry, school and church, hotel, accommodation house. Hall also questioned whether it would support a dairy factory.

Letter to John Fountaine 14 January 1886:

The best thing for New Zealand farmers to go in for, I believe to be Dairy Factories and Dairy produce. It will

not fetch a high price, but I do not think in this article we are likely to be edged out by Australia, or North or

South America. Besides it will give employment to the ‘coming race’ of New Zealanders, which wool and

mutton growing will barely do. I often wonder whether Hororata would support a Dairy Factory? but am

afraid the milk suppliers are too few and too scattered.

12 years later is a report in the Ashburton Guardian 15 March 1898:

The committee of the A & P Association [of which John was a member] decided today to call a conference

of delegates from the County Councils and public bodies taking an interest in irrigation with a view to

collecting information for formulating a scheme and bringing pressure to the government to assist in the

irrigation of the Canterbury Plains.

16 March 1898: The Progressive Liberal Association on Monday passed a resolution to the effect that it

would be inequitable to spend public money on irrigation of which the chief immediate result would be to

enhance the value of land owned by private persons.

It is interesting to note that now, in the second decade of the 21st century, a large scale irrigation scheme is being developed on the Canterbury Plains and that dairying has largely taken over from sheep farming.

Reference has been made that John Hall’s attachment to the station 'governed his politics and sustained his soul'. I believe it means that his interaction with his employees and his participation in a rural community, gave him the knowledge of what was needed in the political decisions being made at the time. I like to think that when John spent time at Hororata he could remove himself a little from the worries of parliament.

In the 1870s and 80s John was involved with the Hororata Domain; land for the Public Hall was given by him; he was very involved with St John's Anglican Church; he was always interested in the school and generous towards it. The school picnic was often held at his homestead or, if wet in the woolshed. When the 1906 International Exhibition was held in Christchurch, he gave each child at Hororata school a half-crown to spend. In his will he left money for swimming baths, which weren’t built until the 1920s and were one of the earliest in rural schools. As was common for those colonists, he was not a swimmer, and I think had an unfortunate experience crossing the mighty Rakaia River. He presented a shield for lifesaving and this is still competed for by Christchurch schools.

John Hall was an energetic man, hard working and with wide interests; he was compassionate, generous and approachable; a quietly passionate man for causes he believed in. He knew he had lived through interesting times, and wrote about some of them. At the end of his life he employed a secretary who lived at Terrace Station and his papers were ‘put in order’. His personal diaries were typed; newspaper cuttings were organized into a collection of 100 volumes. John was a phenomenal keeper of records, and we are fortunate that these still exist.

.