SIR JOHN HALL AND WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE

written by Dr Jean Garner

Sir John Hall was the central figure in the history of women winning the vote. He was the leader of the parliamentary campaign for female enfranchisement. His contribution was important because only men had seats in the General Assembly and only they could enact legislation.

Hall was well qualified to head the parliamentary campaign. He had been a member of the Canterbury Provincial Council for most of its existence and had served in both houses of the general Assembly. He had first sat in the House of Representatives in 1856 and had held cabinet rank several times. He had been premier from 1879 to 1882. His long and distinguished career in politics meant that he was well-versed in the factional manoeuvres necessary to pass legislation through the Assembly.

Hall’s support for women’s suffrage was well established before he undertook to guide the measure through parliament. At the end of the 1870s, he had backed the introduction of female franchise in both houses of the General Assembly. As a member of the Legislative Council in 1878, he had declared himself in favour of votes for all women and when he returned to the House of Representatives in 1879, he had once again supported female enfranchisement.

Several years later, then, when Kate Sheppard, the women’s leader, was looking for a politician to promote the suffrage cause in parliament, Hall was an obvious person for her to approach. She lived in Christchurch and knew that he was not only a supporter of women’s enfranchisement but that he was by far Canterbury’s most able and prominent politician. She wrote to him in 1888, asking him to be the women’s parliamentary advocate and, since her request was in keeping with his own position on votes for women, he accepted immediately.

Hall himself was aware that he possessed another advantage which he could exploit to advance the suffrage cause. Some people considered that votes for women was a ‘radical’ idea; one which would turn their world upside down. They shuddered in the face of such ‘a leap in the dark’. Hall was familiar with this kind of reasoning against the extension of the suffrage but made it clear that such arguments were ill-founded. Being small in stature himself, he did not look threatening. In 1890, when he was sixty-five years old, not an age usually associated with extreme ideas, he pointed out to his parliamentary colleagues that they should ‘find the fact that the proposal [to introduce votes for women] is made by an old man who is not an inexperienced politician some assurance that it is not a rash or dangerous proposal.’

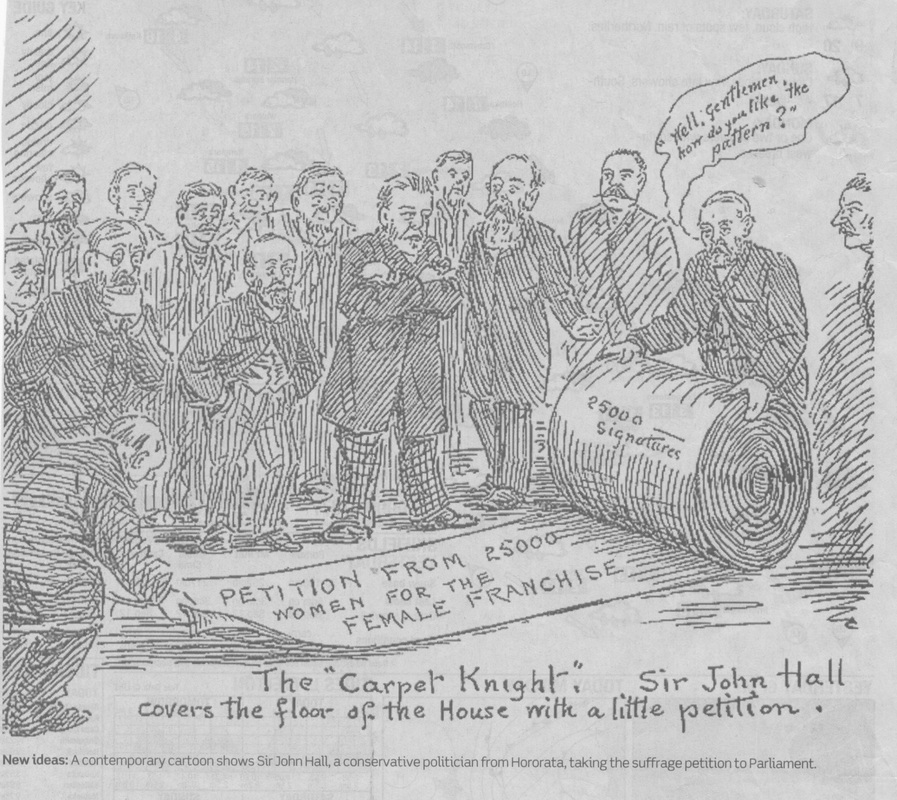

Hall became the chief strategist of the campaign to enfranchise women in the five years 1888 to 1893. In the House of Representatives, he used various methods to advance the cause. These were increasingly successful. Their effectiveness, however, rested to a large degree on his tailoring of the activities of the women’s movement to meet the requirements of the parliamentary campaign. Hall corresponded with Sheppard and several of the colony’s leading suffragists. He offered valuable tactical advice so that their efforts would be as effective as possible. In particular he stressed the importance of collecting signatures for the mass petitions which he would present to the House of Representatives. These petitions from women throughout the colony demonstrated conclusively that women did want the vote. When the number of signatories increased by ten thousand names each time that a petition was undertaken, it put pressure on the politicians. They could no longer avoid making votes for women a high priority. The suffrage petitions played a significant part in the passing of legislation to extend the vote to women.

Hall’s involvement with women’s rights, however, did not end on 19 September 1893. He used his position as a leader in the successful New Zealand campaign to advise those working to enfranchise women overseas. In particular, he corresponded with suffragists in the Australian colonies and in England. Visiting Britain in 1894, he was a popular speaker on women’s suffrage and it was one of the topics on which he was invited to address the colonial committee of the House of Commons.

More important, in his later years, were Hall’s efforts to win the ecclesiastical vote for Anglican women. As in the parliamentary campaign, Hall was well qualified to promote the cause. His own faith was very important to him. As a young man in Britain he had considered seeking ordination in the Church of England. In New Zealand, he had been a member of both diocesan and general synods. In 1859, he had been at the general synod which had passed the constitution of the Anglican church. In his own parish of Hororata, he had been a lay reader for many years. He was, then, a leading member of the laity.

Hall found it anomalous that although women had won the parliamentary vote in 1893, they could neither vote nor speak at parish meetings. He appreciated how much work women did for the church and began his campaign in 1895 at the general synod in Nelson. He had the backing of the laity but the bishops and clergy firmly resisted the reform. Once again Hall’s ally was Kate Sheppard who wrote letters to the newspapers and watched synodical proceedings from the gallery. Hall did not live to see the introduction of this reform. It was adopted in 1919, twelve years after his death.

**************************************************************************************************************************************************

SIR JOHN HALL – champion of the Women’s Suffrage movement

Kate Foster, a great grand-daughter, spoke at the National Library 28 September 2017. In her talk Kate delved into the character of a man who rose to be Premier of New Zealand, and asked questions as to why he was such a promoter of women’s suffrage. The following article is adapted from her talk.

John was a Yorkshireman, from a Hull sea-faring family though he did not go to sea as his brothers did. Their father and grandfather were sea captains and elder brethren of Trinity House Hull.1 John was born in 1824. His father George had been a prisoner during the Napoleonic Wars and escaped back to England, due to being able to pass himself off as a Frenchman. He thought it vital that his children speak the continental languages. So it was that from the age of 10 John was educated in Switzerland, France and Germany. Aged 83, John recalled and wrote that the first school he attended, when he was 6 or 7, was a boarding school with twelve pupils not far from his home. The people who ran the school were dissenters and settled the question of public worship on Sundays by taking the boys to the Parish Church in the morning and the Dissenting Meeting House in the afternoon. Then aged 10 off to school in St Gallen, Switzerland and again as an old man he recalled that there were only two people who could speak English. They washed winter and summer in the fountain in the town square. Then schooling in Paris and Hamburg. By today’s standards his academic education was limited, but not so his broader life education.

At age 16 John started work in London in a German merchant’s office. He was fluent in French and German which were useful attributes in what was, until the 1850s, the largest city in the world. He then moved to the General Post Office becoming secretary to the Postmaster General. This was a good job but with few prospects of promotion without patronage.

John would have known about the opportunities in New Zealand; the Canterbury Association was being promoted in London. He would have done considerable research before deciding to emigrate. In 1852 John sailed from England on the Samarang, the last of the Canterbury Association ships. The ship's weekly newspaper was called The Soottee Sammee. It was handwritten and eventually comprised six sheets of foolscap per week. Some of the editorials were written by John. In one he gave reasons for different groups of people wanting to emigrate. I think he describes himself:

Lastly we come to the gentleman whose capital has hitherto sufficed to bring up a family in a manner befitting his station,

but who can see no prospect of being able to settle his children on the same footing, and to the younger son of such a

family who prefers rural pursuits to the drudgery of an office, and honest exertion in a community where labour is no

disgrace, to the really degrading situation of a dependent or hanger-on upon friends and relatives at home. Individuals of

this class, not driven from home by the pressure of adverse circumstances, may reasonably look forward to occupying a

prominent position in their adopted country.

John certainly was not averse to hard work and set to with energy to secure a run for himself and his brothers who arrived within a year. He set off on horseback with two fellow passengers from the Samarang and spent two weeks exploring central Canterbury, even venturing to the ‘trans Rakaia wilderness’ as the land to the south of the mighty Rakaia river was known. After further explorations in the North Island, a run on the north side of the Rakaia river was taken up and a short farming partnership with his brothers undertaken. Then they went their separate ways with the run, now owned solely by John, leased out until 1861. That year he returned to England where he married Rose Dryden, sister to his brother George’s wife, Agnes.

Almost immediately after his arrival in NZ, John had become involved in politics. There is an extensive résumé of his political career in Te Ara -The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Perhaps his defining contribution was the active support he gave to the Women’s Suffrage movement. The previous article by Dr Jean Garner, biographer of John Hall, tells of his role in relation to suffrage.

But what was within this man that should make of him such a supporter of women’s suffrage? Perhaps the women in his life played an important role. Though not his wife Rose; I don’t see her as a driving influence. Rose was a shy woman, not one for the centre of attention. As she wrote to her sister in law, “Like Papa I am very much of a stay at home”. Jean Garner refers to a letter written by Kate Sheppard to Rose, asking if she would have her name heading the petition. Rose declined but her name was at the top of the Hororata section. However, in John’s early family life there are stronger female influences. His mother, Grace, died when John was two, leaving four young children and a husband often away at sea. Despite the custom of the age, Grace’s family money was not left to her seafaring husband but to her children in trust and was looked after by Aunt Mildred, Grace’s sister. Aunt Mildred, with no children of her own, then left her money to her nephews and niece. In 1861 John’s sister Grace married, aged 36, by which time she would also have inherited Aunt Mildred’s money. Seemingly following family example, a solicitor drew up a marriage settlement deed – Grace’s inheritance did not go to her husband when she married. Much later, in the 1880s, a niece of John and Rose, Aggie Wakefield was divorced by her husband. Legally, she was the guilty party. Part of the settlement was that she could never see her children again. John stayed in close contact with Aggie, visiting her children and reporting back to her. John knew that women were not always fairly treated and that they were capable of managing their own affairs.

Further, there was his early schooling not following the confines of English tradition. By the time he left school John had had more challenging experiences and was surrounded with more ideas than many people have within a lifetime. John was obviously an intelligent and well-read man, as is evidenced by his extensive library at Terrace Station3. He was a keen follower of John Stuart Mill who had presented a Bill for women’s voting rights to the House of Commons in London in 1866, and again in 1867. I have a leaflet, An Appeal to the men of New Zealand, published in 1869 by Mary-Ann Müller who used the pseudonym ‘Femmina’. This copy was given to John Hall, presumably after the New Zealand Bill was passed in 1893, with the following words, “With the author’s deep gratitude to Sir John Hall, New Zealand’s Stuart Mill.” A copy was also given to Kate Sheppard with a similar note.

Did he act for political motives? I think not as he was due to retire and was not looking for votes in an upcoming election. He was in fact the oldest member of the House of Representatives and had indicated his retirement at the beginning of 1893. In my opinion he was a committed politician who wanted equality for all people, not just women.

From all his early experiences and wide reading we can see that John Hall was not a person locked into a single family, regional, geographic, or cultural way of thinking. Perhaps it is this that made him the right person to lead the struggle within the House of Representative that in 1893 gave to New Zealand women the right to vote.

1.Trinity House Hull, a guild of masters, pilots, and seamen that, among other things, serves seafarers and their families.

See http://www.trinityhousehull.org.uk/

2. Jean Garner, By His Own Merits: Sir John Hall - Pioneer, Pastoralist & Premier Dryden Press, Hororata, 1995

3. His home at Hororata where Kate Foster and her husband Richard now live.

**************************************************************************************************************************************************

In the Terrace Station archives are two bound volumes of newspaper cuttings, 1887-93 and 1893-94, a collection of women’s suffrage pamphlets and papers from New Zealand and other countries, and a parchment copy of the Women's Suffrage Bill.